The Sutlej-Yamuna Link (hereinafter “SYL” for brevity) Canal dispute has a long, complicated and sensitive history, with the genesis of the dispute being traced to the formation of the State of Haryana when it was carved out of the State of Punjab in 1966. The SYL Canal is a 214 km long canal devised for the purpose of sharing of the waters of rivers Ravi and Beas between Haryana and Punjab. A brief history would put the context of the discussion in proper order. It was erstwhile Prime Minister Indira Gandhi who, on 08th April, 1982, launched the construction of the SYL Canal with a ground-breaking ceremony in the Kapoori village in Patiala district. In the stretch of 214 km that was to be constructed, 122 km was to be constructed in Punjab while 92 km was to be constructed in Haryana. However, soon thereafter, agitations, in the form of ‘Kapoori Morcha’ across Punjab broke out against the construction of the SYL Canal. The agitations were being spearheaded by the Akalis. In July of 1985, the erstwhile Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and the erstwhile Akali Dal chief Sant Harchand Singh Longowal signed the “Settlement Accord” whereby they agreed for a new tribunal to assess the availability and sharing of water. Thereafter, the ‘Eradi Tribunal’ is formed under the leadership of Justice V Balakrishna Eradi. In less than a month after the signing of the “Settlement Accord”, Longowal is killed by militants.

Before moving ahead, it would be apt to summarily recap the water-sharing allocations. The Central government, a decade after reorganisation, issued a notification allocating 3.5 MAF (Million Acre Feet) out of the 7.2 MAF that was originally allocated to undivided Punjab back in 1955. Pursuant to the 1981 reassessment, it was assessed that the water flowing down from rivers Ravi and Beas was 17.17 MAF of which 4.22 MAF was allocated to Punjab, 3.5 to Haryana, and 8.6 MAF to Rajasthan. Now, fast-forward to 1987, the Eradi Tribunal recommended an increase in the water-sharing allocation of Punjab and Haryana to 5 MAF and 3.83 MAF, respectively.

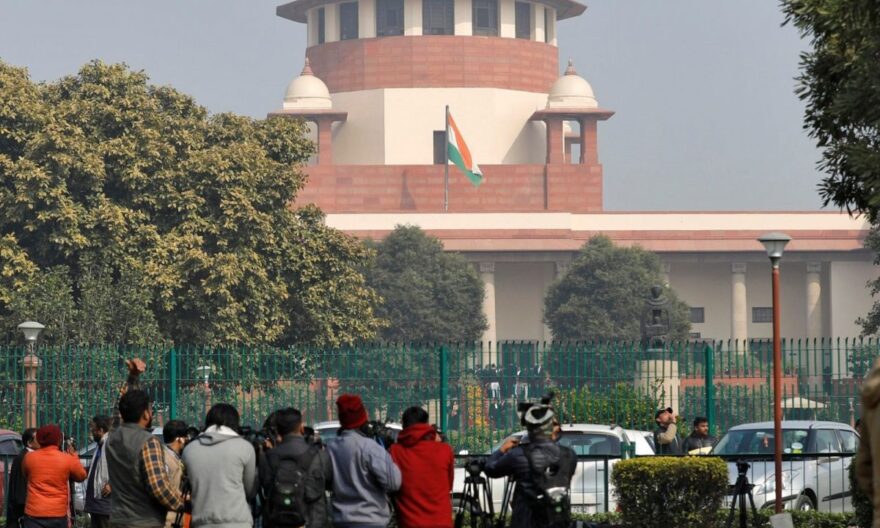

In 1990, the engineers and executives who were involved in the construction of the Canal were killed by militants bringing the construction of the project to a halt. Owing to the tense state of affairs, the Punjab political leaders cautioned the Centre against raking up the issue of the SYL Canal again given the sensitive nature of the issue. However, in 1996, the Haryana government moved the Supreme Court to issue directions to the Punjab government to finish the SYL Canal construction work, which resulted in a long and convoluted litigation.

In 2002 and 2004, the Supreme Court directed the Punjab government to complete the SYL Canal construction work that is pending within its territory. In 2004, the Punjab government passed the Punjab Termination of Agreement Act, 2004, whereby it terminated the water-sharing agreements and consequently jeopardised the construction of the SYL Canal in Punjab. In 2016, the Supreme Court ordered that status quo should be maintained on the SYL Canal, consequent to an application filed by the Haryana Government alleging that attempts have been made to alter its use by levelling it. Additionally, the Court observed that an effort was being made to circumvent the execution of the decree of the Court. The application filed by the State of Haryana had also mentioned the Punjab SYL Canal (Rehabilitation and Re-vesting of Proprietary) Bill, 2016, was passed by the Punjab Assembly which was meant to undo the effects of the Supreme Court’s earlier verdict, wherein it held in favour of the unhindered construction of the SYL Canal which would enable the sharing of its water with Haryana.

Thereafter, later in 2016, the Supreme Court unanimously held that the Punjab Termination of Agreement Act, 2004, which terminated the SYL Canal water sharing agreement with the State of Haryana and other neighbouring States as unconstitutional. The Court observed that any unilateral termination of the 1981 water-sharing pact would be, keeping in view of the law laid down by the Supreme Court in the matter of State of Tamil Nadu v. State of Kerela & Anr., (Original Suit No. 3 of 2006), declared contrary to the Constitution of India as well as the provisions of the Inter-State Water Disputes Act, 1956.

Thereafter, in 2020, the Supreme Court directed the Chief Ministers of both States to negotiate and settle the SYL Canal dispute, and the same was to be mediated by the Centre. Punjab had demanded the constitution of a fresh tribunal to assess the water availability in the State, citing that the water levels have fallen down to 13.38 MAF from 17.17 MAF.

Presently, the inter-state water disputes are one of the most contentious issues concerning Indian federalism. Article 246 of the Constitution deals with the subject-matter of laws that are to be made by the Parliament and by the Legislatures of the States. The allocation of responsibilities between the Centre and States in respect of the laws to be made falls under the three lists enumerated in the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution of India. Entry 17 of the State List in the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution deals with the subject of water, that is, water supply, irrigation, canal, drainage, embankments, water storage and water power, however, this is subject to Entry 56 of the Union List in the Seventh Schedule. Entry 56 of the Union List in the Seventh Schedule of the Constitution empowers the Union government to regulate and develop inter-state rivers and river valleys to such an extent which is considered by Parliament to be expedient in the public interest.

Article 262 of the Constitution deals with the subject-matter of disputes relating to water. It states that Parliament may by law provide for the adjudication of any dispute or complaint with respect to the use, distribution or control of the waters of, or in, any inter-state river or river valley. It also provides that Parliament may by law provide that neither the Supreme Court nor any other court shall exercise jurisdiction in respect of any such dispute or complaint as mentioned in the aforementioned provision.

The resolution of water dispute is governed by the provisions of the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act, 1956. In Section 14 of the Inter-State River Water Disputes Act, 1956, it exclusively provides for the constitution of the Ravi and Beas Waters Tribunal; whereby the current dispute concerning the SYL Canal was also governed by it.

Now, equipped with the above exposition of the facts and circumstances, it would be appropriate to assess the situation. Given the sensitivity of the issue and the compelling political and other vested interests of various stakeholders, it has resulted in a situation where the political machinery which is otherwise competent is unable to take concrete and courageous solutions in order to pave the way forward, owing to apprehensions of backlash from the electorate and consequent political repercussions.

In such a situation, where there are massive stakes involved concerning the general public interest, it is expected that States would not be bogged down by myopic reasons centred around fealty to one’s own particular State at the detriment of other neighbouring States. The States, inclusive of the political machinery as well as the electorate, need to reflect on the value system that they want to inherit for their state polities for the future and consequently develop a matured response as to go about finding a mutually acceptable solution which also offers real and genuine reliefs to each other. The same is only possible when a matured polity is present which can be made possible by few courageous statesmen on either side so as to arrive at a solution with acceptable compromises and devising means to possibly evade the dreadful future that is being apprehended by the general populace. It is extraordinary statesmanship which fosters the circumstances allowing for bright and ingenious ideas to germinate, which may lead to better and innovative means of living.

It must be seriously considered that the right to water, for various needs and purposes, ranging from irrigation and farming activity requirements in the rural context to drinking water and sanitation in the urban context, is a basic human right which is also a fundamental right enshrined under Article 21 of the Constitution of India. There are various global instruments and international covenants which recognise right to water as a basic human right that is to be afforded to every human. The UN Charter and the United Declaration of Human Rights implicitly recognised the right to water as being components of the general quality standard of living that should be provided to every human being. The Geneva Conventions and Protocols explicitly recognises a right to water, however, the same is focused on drinking water. The 1966 Covenants (ICCPR and ICESCR) both implicitly recognise the right to water. The Declaration on the Right to Development also recognise right to clean water as fundamental human right. CEDAW and the Convention on the Rights of the Child also recognise the right to water as basic human rights. In this light, it is heartening to note the recent observations of the Supreme Court on the issue of the SYL Canal dispute, wherein Justice Kaul, heading a three-judge Bench, addressing both Punjab and Haryana, said that, “Water is a natural resource and living beings must learn to share it, whether it be individuals, States or countries…There is a shortage. But if you look at it only from the point of view of the State, then somebody will look at it from the point of view of the city…Then what will happen? I know there are sensitive issues in the State (Punjab), but some calls have to be taken. In the larger interest of the country, you have to sit down and work it out. It cannot be left as a festering wound. Water is a natural wealth to be shared. How it has to be shared is a mechanism to be worked out. We expect parties to work out a way to share the national wealth”.

Therefore, keeping in mind the above considerations, it is pertinent to acknowledge the fact that while the stakes in the SYL Canal dispute are high and it is also a sensitive issue which may be influencing the political leaders to act in favour of the vested interests of their own States in exclusion to the reasonable accommodation of the rights of the neighbouring countries but it is far more important that these serious issues merit a response which goes beyond myopic reasons and interests, so as to protect the larger public interest at stake. In case the political machinery fails to devise a mutually acceptable solution, then the Supreme Court will have to step in and function as the final arbiter of the dispute given the magnitude of rights at stake. It would also be prudent to note that in case it ultimately falls to the Supreme Court to finally decide the dispute, then it must also be cautious of the composition of the Bench that would be constituted to decide on the matter including the composition of any expert committee of technocrats and experts that may be formed to aid the Supreme Court, so as to avoid any unnecessary speculations on the impartiality of the decision, the sentiment of which is best echoed by the age-old aphorism that, “Justice must not only be done, but must also be seen to be done”.

The author is a lawyer and tweets @j_bhoosreddy99.

The post TRACING THE CONTOURS OF THE SUTLEJ-YAMUNA LINK CANAL DISPUTE appeared first on The Daily Guardian.