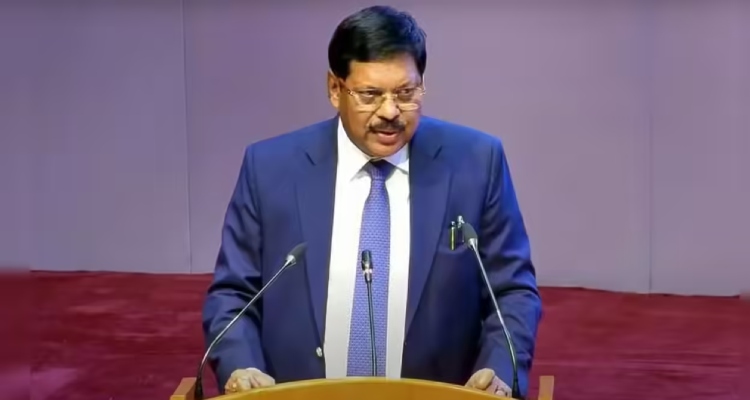

Chief Justice of India (CJI) BR Gavai on Thursday cautioned that “judicial activism should never become judicial terrorism or judicial adventurism.”

The observation came during the presidential reference hearing that raised critical constitutional questions on whether courts can impose timelines for governors and the president to act on bills passed by state assemblies.

The bench, which also included Justices Surya Kant, Vikram Nath, P S Narasimha and A S Chandurkar, was hearing arguments from Solicitor General (SG) Tushar Mehta on the 3rd consecutive day of proceedings.

Debate Over Role Of Elected Leaders

During the hearing, Mehta stressed the importance of respecting elected representatives. “Elected people belonging to whichever political party have to nowadays respond to voters directly. People now directly ask questions from them. Unlike 20–25 years back when things were different, voters are aware and cannot be taken for a ride,” he said.

Responding to him, CJI Gavai clarified, “We never said anything about the elected people. I have always said that judicial activism should never become judicial terrorism or judicial adventurism.”

Context Of The Case

The reference stems from questions raised about whether courts can direct constitutional authorities to adhere to fixed timelines in dealing with state bills.

A day prior, the court held that a governor cannot forward a bill to the president for reconsideration if the state assembly has already re-passed it after being returned once. The bench also noted that it was exercising advisory jurisdiction under Article 143(1), not appellate jurisdiction, while considering preliminary objections by the Tamil Nadu and Kerala governments.

President’s Reference Under Article 143(1)

In May, President Droupadi Murmu invoked Article 143(1) to seek the Supreme Court’s opinion on whether judicial orders could impose deadlines for the president’s discretion in dealing with state bills. In her 5-page reference, the president posed 14 questions relating to the powers of governors and the president under Articles 200 and 201 of the Constitution.

This came after the apex court, in an April 8 judgment on the Tamil Nadu Assembly bills, for the first time prescribed a 3-month period within which the president must decide on bills reserved for her consideration.

Centre’s Stand

In its written submission, the Centre argued that mandating such timelines would allow one organ of the state to assume powers not granted to it by the Constitution, potentially creating “constitutional disorder.” Mehta further submitted that “withholding assent” by a governor is a complete constitutional function in itself under Article 200.

The hearing will continue, with senior advocate Kapil Sibal expected to present submissions. The outcome of the presidential reference is likely to have far-reaching implications on the delicate balance between the legislature, executive, and judiciary in India’s constitutional framework.

Read More: Supreme Court, Delhi High Court, States High Court, International