The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Korea has recently announced its decision to initiate investigations into an additional 237 cases involving South Korean adoptees.

These adoptees, who suspect that their family origins were manipulated to facilitate their adoptions in Europe and the United States, reside in 11 different countries, including the United States, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. The commission’s expanded inquiry focuses on adoptees who were adopted between 1960 and 1990. Last year, over 370 adoptees from Europe, North America, and Australia submitted applications requesting investigations into their cases.

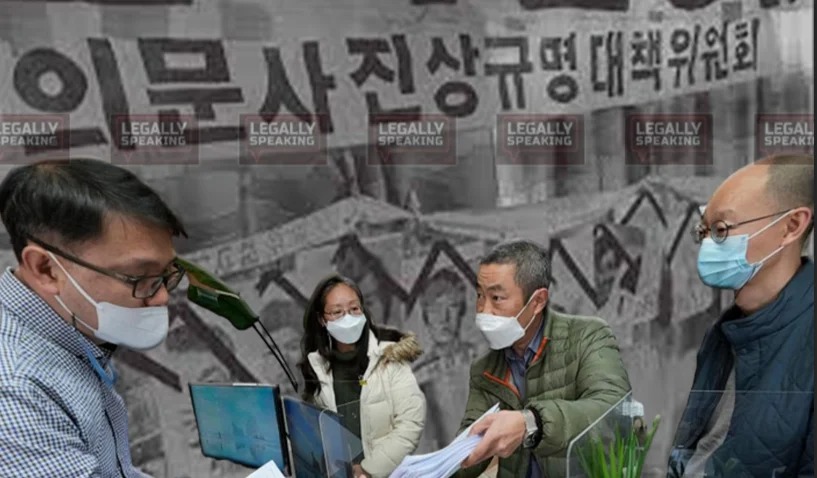

In December, when the commission initially announced its intention to investigate 34 cases, it highlighted that the records of numerous adoptees sent to Western countries had been manipulated. These records falsely portrayed them as orphans or misrepresented their identities by using information from someone else.

According to the commission, the majority of applicants allege that their adoptions were facilitated through falsified records, which distorted their status or origins to make them more suitable for adoption and facilitate cross-border custody transfers. Additionally, some applicants have requested the commission to examine instances of abuse they claim to have endured in South Korean orphanages or while under the care of their adoptive parents abroad.

If the commission uncovers evidence supporting the adoptees’ claims, it could potentially enable them to pursue legal action against adoption agencies or the government. This is particularly significant because South Korean civil courts typically place the burden of proof solely on the plaintiffs, making it challenging for them to gather the necessary information and resources to support their cases.

Out of the 271 cases currently under review by the commission, the majority, 141 cases, involve Danish adoptees. These include members of the Danish Korean Rights Group, co-led by adoptee activist Peter Møller, who initially submitted 51 applications in August of last year. The commission has also accepted cases from 28 U.S. adoptees and 21 Swedish adoptees, among others.

Officials have stated that the commission will likely investigate the remaining 101 cases, continuing to review the applications in the order they were submitted.

Over the past six decades, approximately 200,000 South Koreans, predominantly girls, have been adopted to the West, resulting in what is believed to be the largest diaspora of adoptees in the world.

The majority of South Korean adoptees, particularly during the 1970s and ’80s, were placed with white parents in the United States and Europe. At that time, South Korea was under the rule of various military dictatorships that prioritized economic growth. These governments saw international adoptions as a means to reduce the population and address the perceived “social problem” of unwed mothers, while also fostering closer relationships with democratic countries in the West.

To facilitate the high number of foreign adoptions, the military governments implemented special laws that streamlined the adoption process. However, these practices often bypassed proper child relinquishment procedures. As a result, thousands of children were sent to the West each year during the peak of international adoptions in South Korea.

The majority of adoptees were recorded by adoption agencies as abandoned orphans discovered on the streets, even though many of them had identifiable or locatable relatives. This practice often made it challenging, if not impossible, for adoptees to trace their true roots or find information about their biological families.

It was not until 2013 that the South Korean government implemented a new policy, requiring foreign adoptions to be processed through family courts. This marked the end of a longstanding practice that allowed adoption agencies to have control over child relinquishments and international custody transfers.